Feyerabend: Killing Time at Yale

20.07.2021

In his autobiography Killing Time, Feyerabend recalls the semester he spent at Yale ([1], p. 126):

It has never been clear to me whether I’m being contrasted with the confused and whining sociologists, or lumped together with them.

Yale was my first teaching position, and I owe it to Feyerabend. I was a post-doc at the Minnesota Center for Philosophy of Science when Feyerabend sent the draft of a paper [2] in which he defended Bohr against Popper’s critique of complementarity to Herbert Feigl, the Director of the Center. Feigl asked me to present a report on the paper. I agreed with Feyerabend’s analysis and added some observations. Feigl sent my report to Feyerabend, who invited me to Berkeley to give a talk to a seminar on quantum mechanics he was teaching at the time. I don’t recall what I talked about, but presumably it was a successful visit because Feyerabend persuaded Yale to offer me a junior position in physics and philosophy. So we both arrived in New Haven in the Fall of 1969.

I found the graduate seminar boring too. The first meeting began on a bit of a sour note. There was the usual worry about how grades would be assigned which Feyerabend thought should not be the focus of anyone’s concern, so he proposed finessing the issue by simply giving everyone an A. That didn’t go down well—the class balked at the proposal, on the grounds that it would be unfair to the better students. It was all downhill from there. Feyerabend’s teaching technique was to throw out a provocative comment and wait for an interesting response, but that didn’t work well with this group.

I also attended his undergraduate course, which was quite different. Feyerabend didn’t suggest giving the entire class A’s, but there was no exam and no writing assignment, which he said he wouldn’t be interested in reading anyway. Instead, he proposed assigning grades on the basis of something he could actually use, like a piece of furniture, or something he might actually find interesting, like a short film—or there was the option of taking him to dinner, in which case the grade would depend on the extent to which he found the conversation interesting.

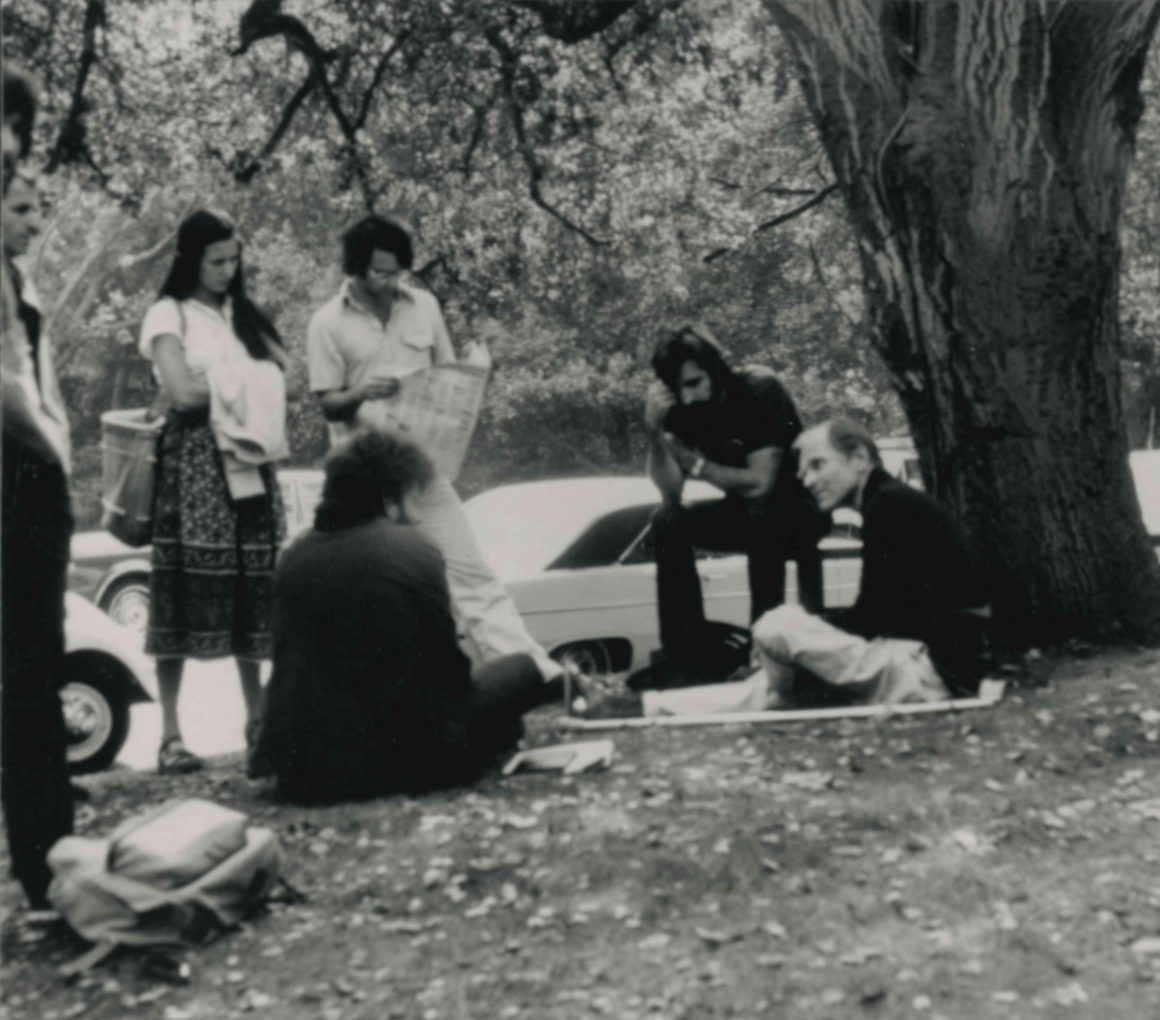

It was the end of the nineteen sixties and New Haven was convulsed with the trial of Bobby Seale and other members of the Black Panther Party. Revolution was in the air and National Guard troops pre-emptively took over the downtown area with tanks. One of the assigned readings for the course was Lenin’s ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder, possibly prompted by the group of Maoist students in red headbands who occupied the front row of the class. After I gave Feyerabend a 12 inch black and white television set that I no longer used, he began each lecture with a discussion of whatever TV program he had watched the evening before, apparently as an anthropological study of American culture. Once launched, the discussion would evolve from something silly to critical issues on philosophy of science or theatre or literature. It was always fascinating.

Feyerabend was often late for his undergraduate class, but the students waited patiently, sometimes for quite a while before he showed up. Once he didn’t show up at all and we waited for almost the entire period. At the next session Feyerabend was unapologetic. The weather was fine, it was the perfect day for a walk in the country, and that’s what he had done, assuming we would all be sensible enough do the same thing rather than sit inside. The class forgave him; there was no revolt, not even from the Maoists.

Feyerabend spent only a semester at Yale before resigning. During the semester he was invited to give several talks at the University of Western Ontario. When he returned he said to me that if I ever wanted a break from Yale, he would suggest to Robert Butts, the Chair of the Philosophy Department, a nice guy with a sign on his desk saying ‘Don’t Throw Butts on the Floor,’ that he should invite me. I did receive an invitation for a visiting position, which I accepted. After Feyerabend left Yale, New Haven lost some of its appeal and I decided to remain at Western Ontario when the invitation was extended to a permanent position.

We occasionally went to lunch together at Hungry Charlie, a lively student hangout with an uninspiring food selection, but Feyerabend preferred it to the more upscale eating establishments frequented by faculty, which he found gloomy. It was self-service and, after choosing a lunch dish, he would hesitate momentarily over the desserts before eventually opting for a large slice of chocolate cake, one of the perennial offerings, more appealing to the eye than the palate. He would take a bite of the cake and then push the rest aside. I asked him why he always chose the same dessert if it turned out to be disappointing each time. He looked at me in astonishment and said ‘Surely you don’t think I believe in induction?’

References

[1] Feyerabend, P. (1996). Killing time: the autobiography of Paul Feyerabend. University of Chicago Press

[2] Eventually published as a 2-part paper. On a recent critique of complementarity, I and II. In Philosophy of Science 35, 309-331 (1968) and 36, 82-105 (1969).